Abstract

Background

Despite society recommendations to limit thrombophilia testing, this testing is often sent inappropriately. The results of thrombophilia testing frequently do not affect management. Additionally, interpretation of thrombophilia testing is confounded by acute thrombosis, anticoagulation (AC) therapy, and other medical comorbidities. Incorrect test selection is also a source of unnecessary testing [i.e. Factor V (FV) activity level instead of Factor V Leiden (FVL)].

The aim of our study was to assess ordering patterns for thrombophilia testing by qualifying the number of tests, identifying the requesting services, and assessing the appropriateness of testing.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of thrombophilia testing performed at LAC+USC Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019. A laboratory query of thrombophilia testing was performed to identify eligible adult patients who received thrombophilia testing without a prior confirmed thrombophilia. Thrombophilia testing included: FVL and prothrombin 20210 gene mutations; activated protein C (APC) resistance; antithrombin, or protein C or S activity levels; and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) evaluation with lupus anticoagulant, cardiolipin (CL) immunoglobulins IgM/G, and beta-2 glycoprotein (b2gp) IgM/IgG; and JAK2 V617F mutation. Homocysteine (HC) levels and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene mutation testing were considered to have limited clinical utility. FV activity and phosphatidylserine IgM/IgG were considered incorrect tests.

The electronic medical record was reviewed for clinical history, indication for testing, requesting service, and appropriateness. The criteria for defining appropriateness were determined based on major society guidelines and literature review. The main criteria are summarized here. Testing was considered inappropriate for a provoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) or stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA). For unprovoked VTE, testing was considered inappropriate for patients > 45 yo except for APS testing. For non-stroke arterial thrombosis, recurrent pregnancy loss or stillbirth, and diagnostic evaluation of suspected lupus, APS testing only was considered appropriate.

Results

450 patients underwent thrombophilia testing with a mean age of 42 (range: 18-90); 76% were female and 81% were Hispanic.

A total of 1698 thrombophilia tests were sent by 27 services. Testing was done in the following settings: inpatient (40%), outpatient (59%), and emergency department (1%). The mean tests per patient were 3.7 (range: 1-12). The most common requesting services were rheumatology (24%), obstetrics-gynecology (19%), and internal medicine/medicine-pediatrics (14%). Hematology requested 10% of tests.

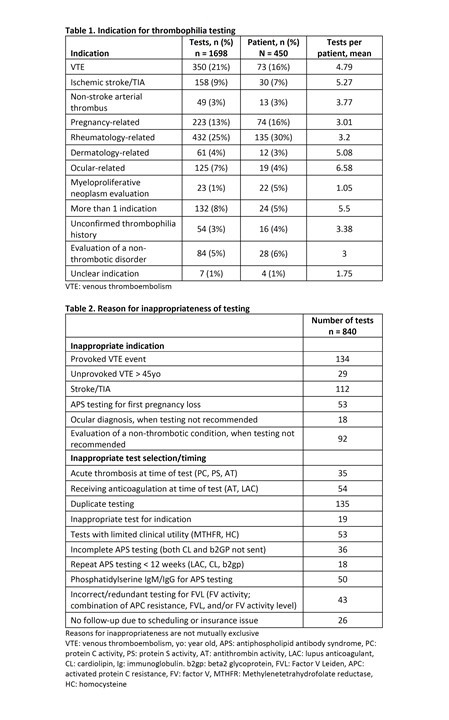

Common indications for testing were VTE (21%), rheumatology-related (25%), pregnancy-related (13%), ischemic stroke/TIA (9%), ocular-related (7%), non-stroke arterial thrombosis (3%), and dermatology-related (4%) (Table 1). 5% (84 tests) were sent for the evaluation of other non-thrombotic conditions. 8% (132 tests) were sent for > 1 indication, such as concurrent arterial and venous events.

840 tests (49%) were deemed inappropriate. Common reasons for inappropriate testing included provoked VTE events, stroke/TIA, APS testing after first pregnancy loss, current AC, and duplicate testing (Table 2). APS testing issues included testing for LAC while on AC, incomplete testing (both CL and b2GP not sent), incorrect tests (phosphatidylserine IgM/IgG), and repeat testing < 12 weeks from prior. Incorrect/redundant testing for FVL included: FV activity levels (36 total tests; 9 ordered in additional to FVL and 27 ordered instead of FVL) and APC resistance ordered simultaneously with FVL in 7 patients. Of note, 92 tests were sent for evaluation of non-thrombotic conditions.

Conclusions

Thrombophilia testing is often done inappropriately. Correct test selection is also a relatively common issue, particularly with APS and FVL testing. Given the large number of services ordering thrombophilia testing at our training hospital and this testing being sent for a variety of reasons, it is unlikely that physician education alone will lead to a substantial or sustained decrease in the number of inappropriate tests. Rather, it may be necessary to restrict at least some thrombophilia testing to certain services.

Piatek: Rigel: Consultancy, Research Funding; Alexion: Consultancy, Research Funding; Apellis: Research Funding; Dova: Consultancy, Speakers Bureau.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal